It is the perhaps the most unusual – and exclusive – museum in the world, filled with artefacts that have shaped history. But its doors are firmly shut to the public.

It is the only place a visitor can see the gun found with Osama bin Laden when he was killed, next to Saddam Hussein’s leather jacket.

Welcome to the CIA’s secret in-house museum.

Located inside the US intelligence agency’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia, the collection has just been renovated to mark the agency’s 75th anniversary. A small group of journalists, including the BBC, were given exclusive access, although with a security escort constantly at our side.

Among the 600 artefacts on display are the kinds of cold war spy gadgets you might expect – a ‘dead drop rat’ in which messages could be hidden, a covert camera inside a cigarette packet, a pigeon with its own spy-camera and even an exploding martini glass.

But there are also details on some of the CIA’s more famous and even recent operations.

On display is a scale model of the compound in which Osama bin Laden was discovered in Pakistan. President Obama was shown a model before approving the raid that killed the al-Qaeda leader in 2011.

“Being able to see things in 3D actually helped the policymakers…as well as help our operators to plan the mission,” explains Robert Z Byer, the museum’s director who provided a tour.

On 30 July this year a US missile hit another compound, this time in the Afghan capital Kabul. The target was the new leader of al-Qaeda, Ayman al-Zawahiri.

And the most recent exhibit, just declassified, is a model of the compound used to brief President Biden on July 1st 2022 on the proposed mission. Zawahiri was hit whilst on the balcony after the US intelligence community spent months studying his movements.

“It speaks to how counter-terrorist officers look to the pattern of life of the target,” explains Mr Byer.

The first half of the museum moves in chronological order from the CIA’s foundation in 1947 through the Cold War, with the 11 September 2001 attacks a clear pivot in the shift towards focusing on counter-terrorism, with items in display donated by some of those whose relatives died in the attacks.

The museum’s audience is the CIA’s own staff as well as official visitors. It does not just focus on success. There is a section on the Bay of Pigs fiasco when a CIA mission to overthrow Fidel Castro in Cuba went disastrously wrong and there are references to the failure to find weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.

“This museum is not just a Museum for history’s sake. This is an operational museum. We are taking CIA officers [through it], exploring our history, both good and bad,” says Mr Byer. “We make sure that our officers understand their history, so that they can do a better job in the future. We have to learn from our successes, and our failures in order to be better in the future.”

Some of the most controversial aspects of the CIA’s work are less visible though – for instance its 1953 joint operation with MI6, to overthrow a democratically elected government in Iran and more recent involvement in the torture of terrorist suspects after 2001.

‘We can neither confirm or deny’

The second half of the museum focuses in detail on some specific operations.

The phrase “we can neither confirm nor deny” is a familiar one for those who report on intelligence agencies and its origins lie in a story detailed in the museum using never seen before items.

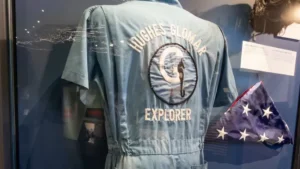

In the late 1960s, a Soviet Union submarine was lost somewhere on the ocean floor. After the US located it, the CIA worked with billionaire Howard Hughes to try and recover the wreck – and the technology on board. A cover story was developed that Hughes was going to mine the ocean floor using a ship called the Glomar Explorer.

The museum contains a model of the Soviet submarine as well as clothing, ash trays and mailbags created to maintain the cover of the Glomar. There is even on display a wig worn by the CIA’s deputy director to disguise himself during a visit to the ship.

The mission was only partially successful because the submarine broke apart as the Glomar’s steel claws tried to bring it up although some parts were still recovered.

“Most of what they found aboard that submarine is still classified to this day,” says Mr Byer.

When news broke of what was known as Project Azorian before the rest of the submarine could be extracted, officials were told to say they could “neither confirm nor deny” what had taken place – a phrase known as the “Glomar response” and still used widely now.

There are also items used to build the cover story for a fake movie called Argo. This would allow the rescue of diplomats held in Iran after the 1979 revolution, a tale later turned into a Hollywood movie. On display is conceptual art for the fake film which the rescue team pretended to be making. The art was designed to be deliberately hard to decipher or understand.

And when it comes to deciphering, the ceiling of the new museum also contains hidden messages in different types of code.

The ambition, CIA officials say, is for images to be shared with the public on social media to see if they can unscramble them. Some of the exhibits will also be available to view online. But for the moment, that may be the closest most people can get to this museum.