Emmanuel Macron is firing up his campaign for re-election, directly taking on far-right rival Marine Le Pen in France’s presidential run-off.

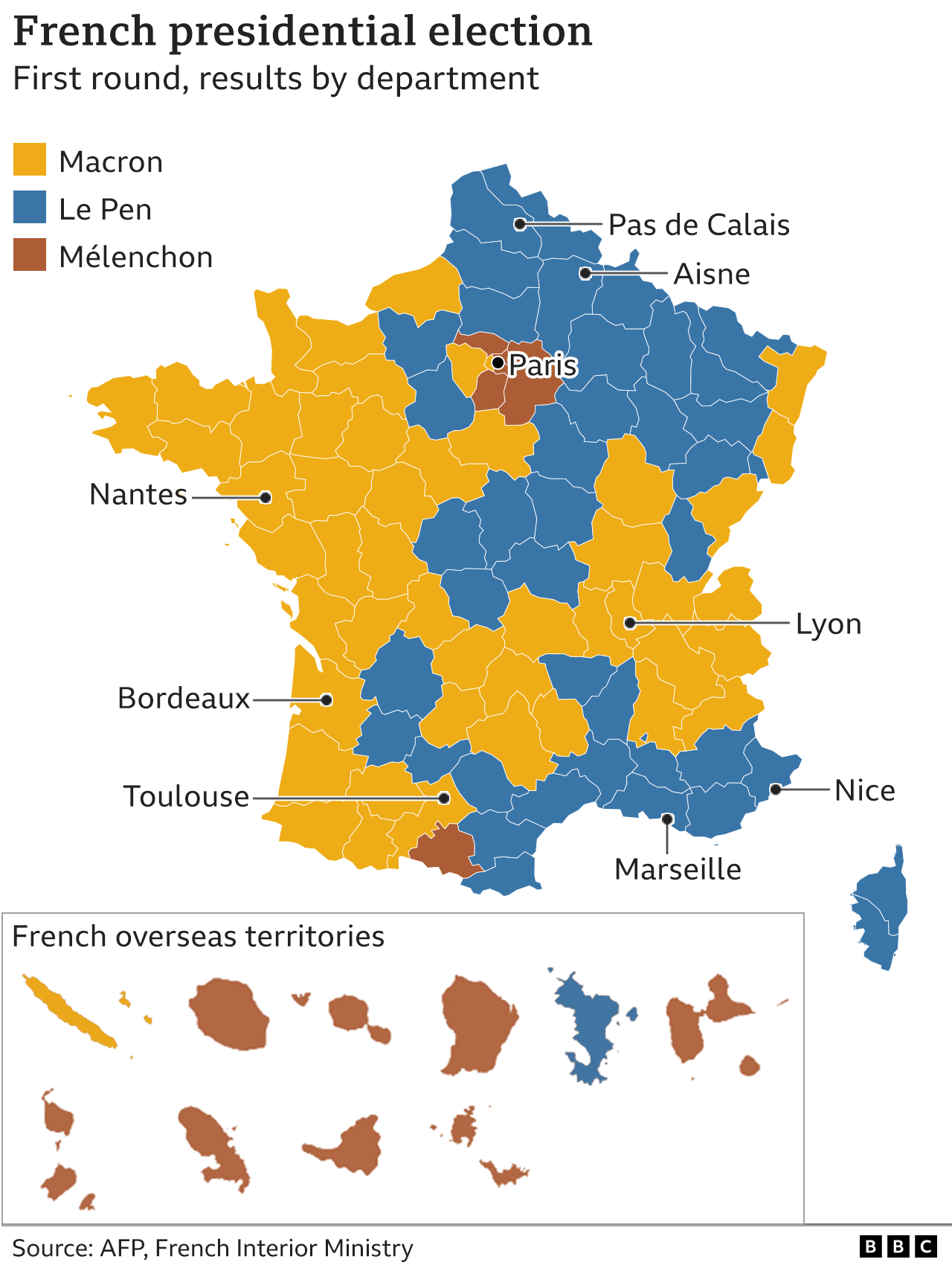

He made his first trip to a Le Pen stronghold at Denain, one of France’s poorest towns in the industrial north.

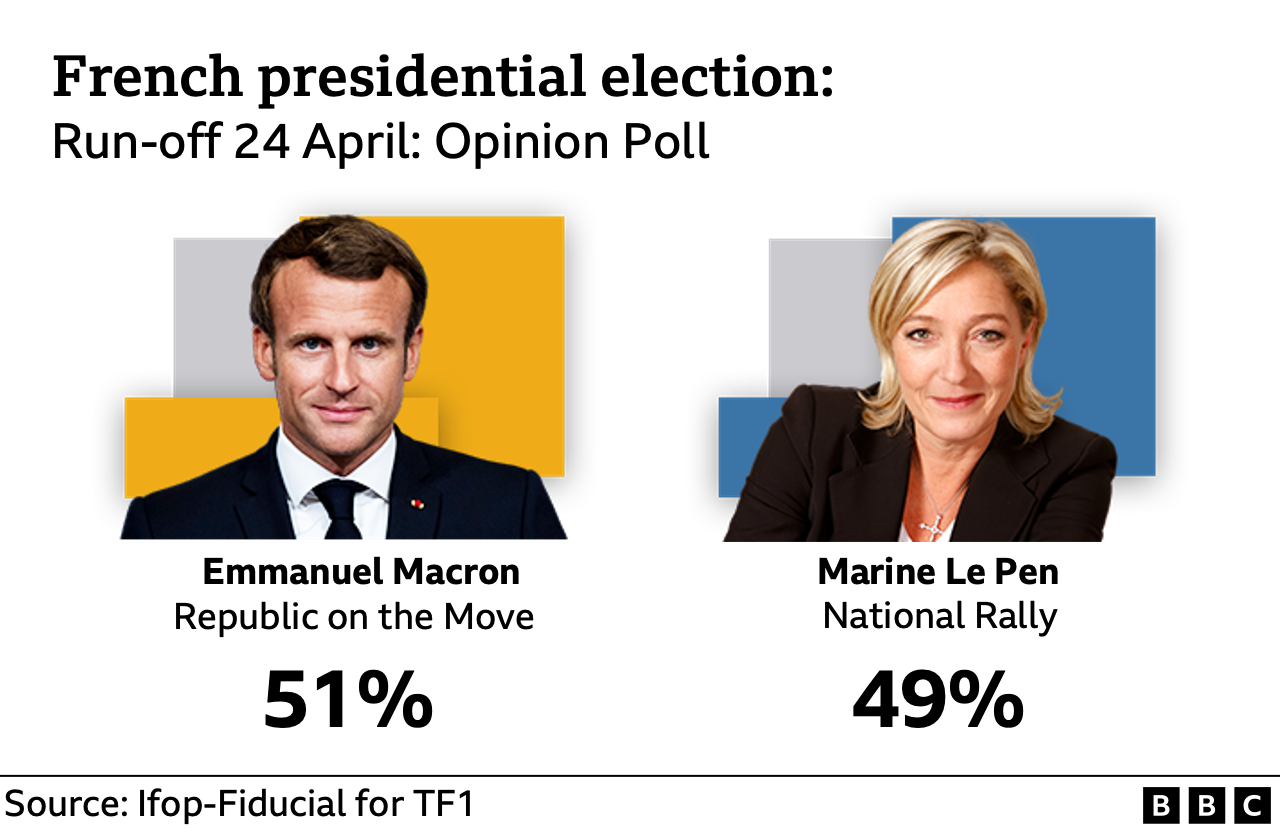

President Macron won the first round of the election, but opinion polls suggest the second round will be a close race on 24 April.

“Make no mistake: nothing is decided,” he told supporters after the vote.

Both candidates polled better than the first round in 2017, but Le Pen officials were in far more buoyant mood the morning after the result, even though she trailed the president by four points.

Jordan Benalla, president of her National Rally party, was confident Ms Le Pen would find willing support from the 70% of people who voted against Mr Macron.

“They know if he gets back in, it’s going to be five more years of social breakdown, fiscal bloodletting, powerlessness over their sovereignty, violence throughout the country and immigration,” he told French radio.

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESThe president acknowledged he had left campaigning too late. He chose to focus instead on Russia’s war in Ukraine, partly in the belief that his role as a statesman would boost his poll numbers.

Meanwhile, the Le Pen team concentrated on the cost of living crunch affecting much of the French population.

“Clearly we’re not listening enough to the 38 million French people who earn less than €2,000 (£1,680) a month,” said Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin.

With that in mind, Mr Macron headed to the northern towns of Denain, Carvin and Lens where the National Rally candidate came out on top.

Another minister, Clément Beaune, said it was an area that had experienced decades of high deprivation and Marine Le Pen was attracting high levels of support. The aim was to spend the next two weeks highlighting the government’s record in creating jobs and reinvigorating industry, he explained.

“Marine Le Pen is all talk about the cost of living and protecting people in most difficulty,” he said. “But in concrete terms what would she achieve for them – and what would we do?”

Tactical voting

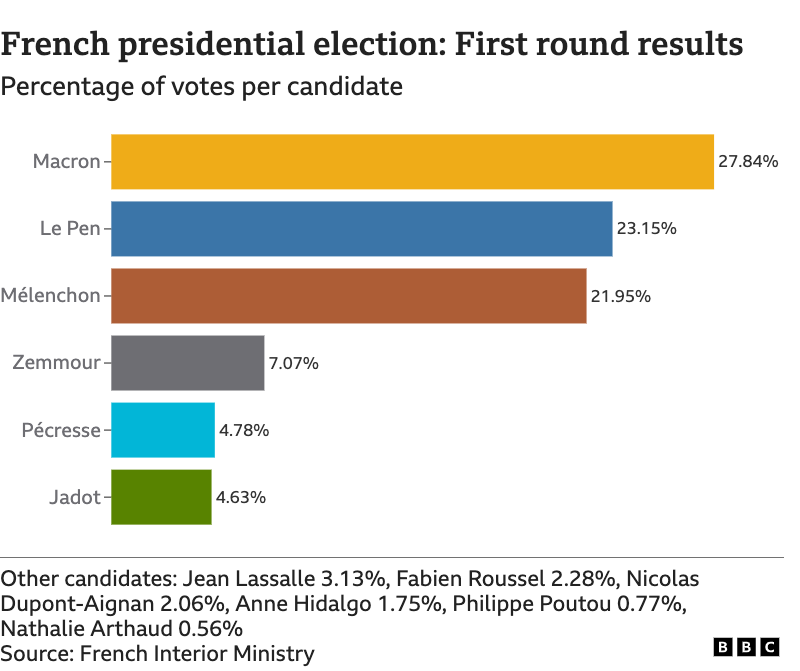

With all of the votes counted, Emmanuel Macron took 27.84% of the vote, Marine Le Pen 23.15% and far-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon 21.95%. Between them they attracted close to three-quarters of the vote, as the electorate largely abandoned other candidates they decided had no chance of making the run-off.

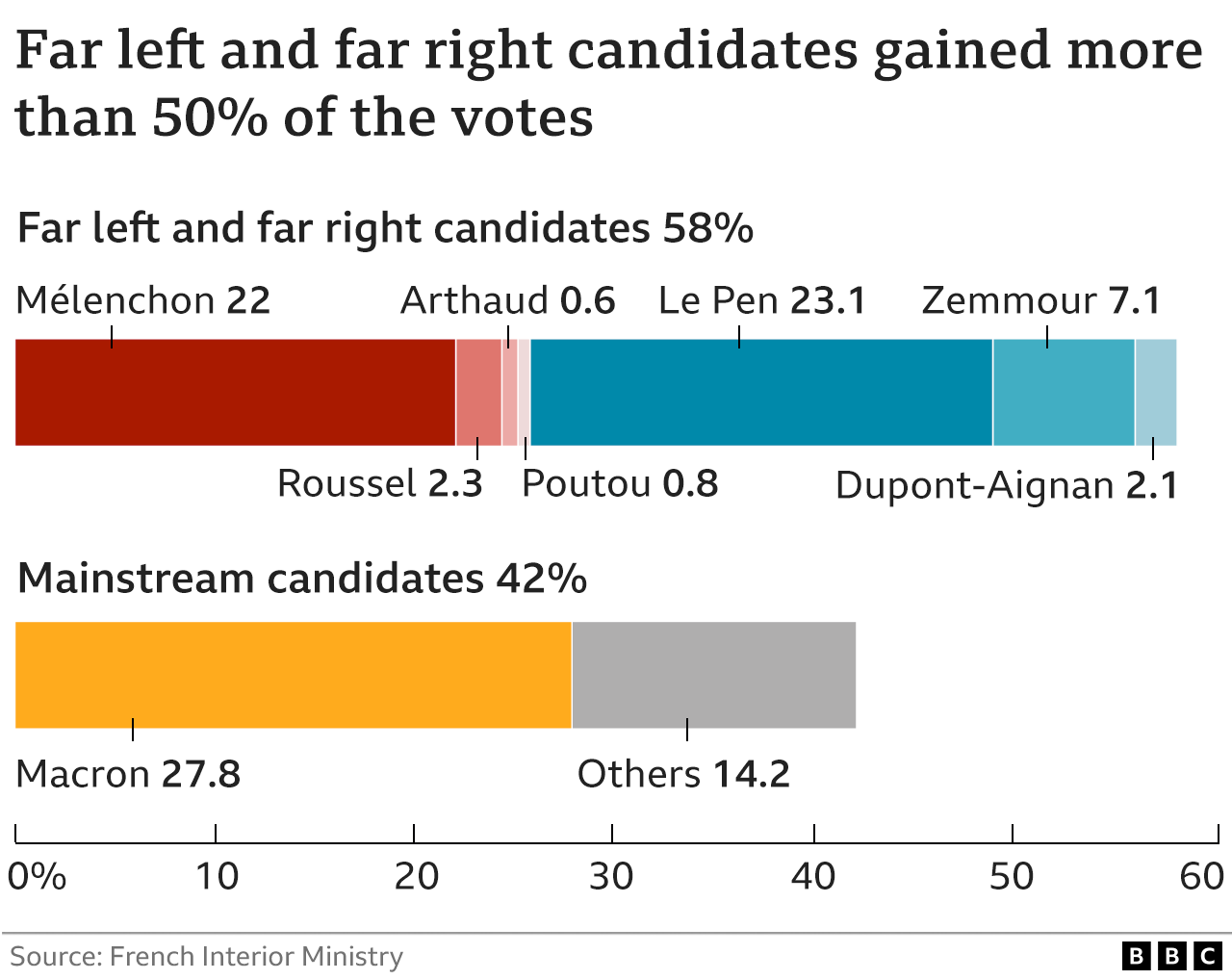

Another of the big revelations on the night was that more than half of voters backed the far right and far left.

Mr Mélenchon was not far behind Marine Le Pen and his voters could decide the final round of this election, if they turn out to vote.

“You must not give a single vote to Marine Le Pen,” he warned his supporters, although he pointedly did not back the president instead.

More mainstream candidates did urge voters to support Mr Macron in the run-off, including Valérie Pécresse from the right-wing Republicans and Anne Hidalgo from the Socialists. Both had an awful night, failing to even scrape the 5% of the vote needed to recoup their election costs.

For Ms Pécresse, this has become a financial as well as a political disaster.

Appealing for donations from supporters, she revealed that her campaign finances were in a “critical state” and that she had used €5m (£4.2m) of her own money.

Meanwhile, the Le Pen camp can count on up to a third of the national vote. She will attract the votes of Eric Zemmour, whose more hardline nationalism won him fourth place with 7%. Nationalist Nicolas Dupont-Aignan has also backed her.

Mr Macron’s team is planning a series of big rallies and major TV appearances, although the big set-piece event is likely to be the TV debate on 20 April.

Ifop pollster François Dabi said his company’s 51%-49% estimate for the run-off was the closest they had ever predicted. An Elabe poll put the gap at 52%-48% and an Ipsos poll suggested it was wider still.

Addressing his supporters, Mr Macron looked a relieved man and he promised to work harder than in the first part of the campaign.

“When the extreme right in all its forms represents so much of our country,” he said, “we cannot feel that things are going well.”

It was already clear from Mr Macron’s speech that in the days ahead he planned to target Ms Le Pen’s close links with the Kremlin. Although she has condemned Vladimir Putin’s war, she visited him before the previous election in 2017 and her party took out a Russian loan.

Ms Le Pen said it was time for a “great changeover”, with a fundamental choice on 24 April of two opposite views: “Either division and disorder, or a union of the French people around guaranteed social justice.”

She has promised to cut taxes and waive income tax for under-30s. There has been less emphasis on nationalism, but she wants a referendum on restricting immigration, radical change to the EU and a ban on the Islamic hijab in public areas.

One in four voters aged 18-24 backed the president and he was most popular among over-65s, while Marine Le Pen performed best among 35-64 year-olds.

Source: BBC News