Images of the bodies of civilians in the streets of Bucha have led to international condemnation of Russia and further accusations that its forces are committing war crimes.

The International Criminal Court has already begun investigating whether war crimes are taking place and Ukraine has also set up a team to gather evidence.

What is a war crime?

It may not seem like it, but “even war has rules”, as the International Committee of the Red Cross puts it.

These are contained in treaties called the Geneva Conventions and a string of other international laws and agreements.

Civilians cannot be deliberately attacked – nor can the infrastructure that is vital to their survival.

Some weapons are banned because of the indiscriminate or appalling suffering they cause – such as anti-personnel landmines and chemical or biological weapons.

The sick and wounded must be cared for – including injured soldiers, who have rights as prisoners of war.

Serious offences such as murder, rape or mass persecution of a group are known as “crimes against humanity”.

What is genocide?

Genocide is defined in international law as the deliberate killing of people from a particular national, ethnic, racial or religious group, with the intention of destroying the group – whether entirely or in part.

As such, genocide is a specific war crime that is bigger than the illegal killing of civilians. The law requires proof of the intent to destroy the group.

The 1994 slaughter in Rwanda of about 800,000 people later led to prosecutions for genocide.

What allegations of war crimes have there been in Ukraine?

Investigators and journalists have found what appears to be evidence of the deliberate killing of civilians in Bucha, a town on the outskirts of Kyiv, and other nearby areas.

Ukrainian forces say they have found mass graves and there’s evidence of civilians having been shot dead after their feet and hands were bound.

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson said the attacks are “yet more evidence” of war crimes.

Last week, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said Russia had “destroyed apartment buildings, schools, hospitals, critical infrastructure, civilian vehicles, shopping centres, and ambulances” – actions that the US said amounted to war crimes.

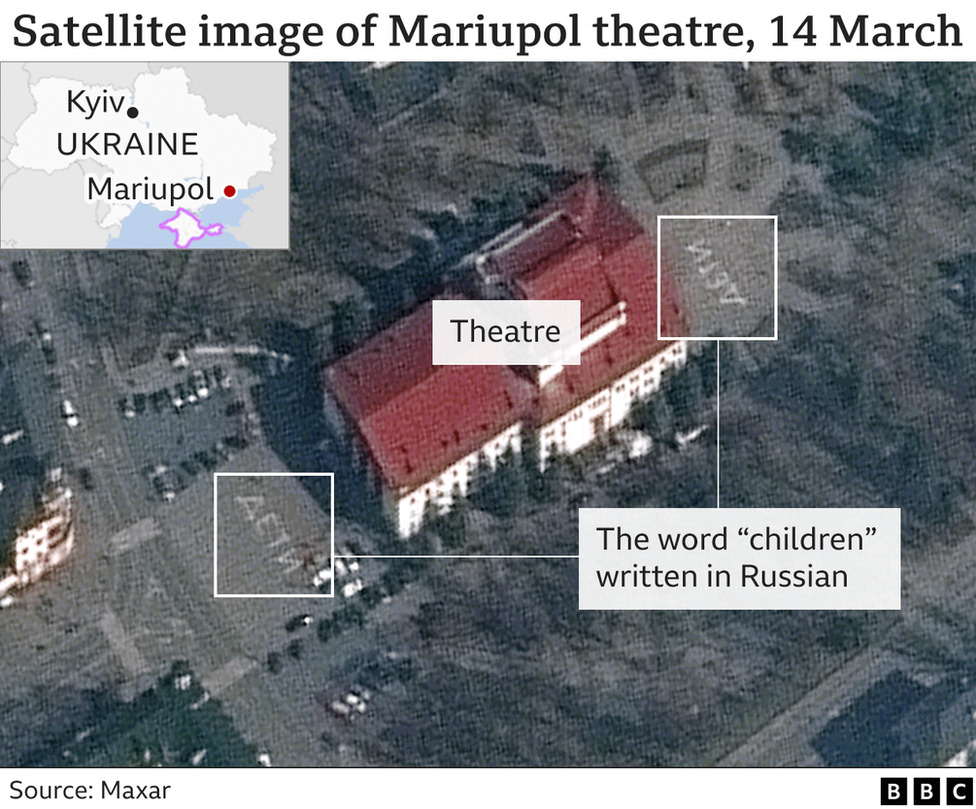

In March, a Russian strike on a theatre in Mariupol, appeared to be the first confirmed location of a mass killing. The word “children” was written in giant letters outside the building.

Ukraine previously called Russia’s air strike on Mariupol’s hospital a war crime.

There’s also mounting evidence that cluster bombs – munitions that separate into lots of bomblets – have hit civilian areas of Kharkiv.

The UK says Russia has used thermobaric explosives, which create a massive vacuum by sucking up oxygen. These are not banned, but their deliberate use near civilians would almost certainly break the rules of war.

Many experts argue the invasion itself is a crime under the concept of “aggressive warfare”.

IMAGE SOURCE,PRIVATE/HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH

IMAGE SOURCE,PRIVATE/HUMAN RIGHTS WATCHHow can suspected war criminals be prosecuted?

There have been a series of one-off courts since World War Two – including the tribunal investigating war crimes during the break-up of Yugoslavia.

A body was also set up to prosecute those responsible for the 1994 Rwanda genocide.

Today, the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ) have roles upholding the rules of war.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) rules on disputes between states, but cannot prosecute individuals. Ukraine has begun a case against Russia.

If the ICJ ruled against Russia, the UN Security Council (UNSC) would be responsible for enforcing that.

But Russia – one of council’s five permanent members – could veto any proposal to sanction it.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) The ICC investigates and prosecutes individual war criminals who are not before the courts of individual states.

It’s the permanent modern successor to Nuremberg, which prosecuted key Nazi leaders in 1945.

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESNuremberg cemented the principle that nations could set up a special court to uphold international law.

Can the ICC prosecute offences in Ukraine?

The ICC’s chief prosecutor, British lawyer Karim Khan QC, says there is a reasonable basis to believe war crimes have been carried out in Ukraine.

Investigators will look at past and present allegations – going back as far as 2013, before Russia’s annexation of Crimea from Ukraine.

If there’s evidence, the prosecutor will ask ICC judges to issue arrest warrants to bring individuals to trial in The Hague.

But there are practical limitations to its power. The court doesn’t have its own police force so relies on individual states to arrest suspects.

Russia is not a member of the court – it pulled out in 2016. President Putin won’t extradite any suspects.

If a suspect went to another country, they could be arrested – but that’s a very big if.

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESCould President Putin, generals or other leaders be prosecuted?

It’s far easier to pin a war crime on the soldier who commits it, than the leader who ordered it.

Hugh Williamson of Human Rights Watch – experts in gathering evidence of war crimes in conflicts – says there is evidence of summary executions and other grave abuses by Russian forces.

He says establishing the “chain of command” is very important for any future trials – including either where a leader has authorised an atrocity – or turned a blind eye to it.

“There’s one interesting episode in our Ukraine report where a commander instructs the soldiers to take out two civilians and shoot them dead,” he told BBC News. “Two of the soldiers object to this and that command is not carried out. So, there’s clear evidence of some incidents in the Russian army, but also a command and control element to it.”

The ICC can also prosecute the offence of “waging aggressive war”. This is the crime of an unjustified invasion or conflict, beyond justifiable military action in self-defence.

It originated at Nuremberg, after the judge sent by Moscow convinced the Allies that Nazi leaders should face justice for “crimes against peace”.

However, Professor Philippe Sands QC, an expert on international law at University College London, says the ICC couldn’t prosecute Russia’s leaders for this because the country isn’t a signatory to the court.

In theory, the UN Security Council could ask the ICC to investigate this offence. But again, Russia could veto this.

So is there any other way to prosecute individuals?

The effectiveness of the ICC – and the way international law plays out in practice – depend not just on treaties, but politics and diplomacy.

Prof Sands and many other experts argue that like Nuremberg, the solution lies once more in diplomacy and international agreement.

He’s calling for world leaders to set up a one-off tribunal to prosecute the crime of aggression in Ukraine.

Source: BBC News