A veteran Nigerian journalist Liad Tella has unveiled a book detailing why his hometown Iwo, in Osun state is yet to benefit maximally in spite of the town’s active participations and massive delivery of votes for previous political gladiators.

Tella, a former News Editor at the PUNCH newspapers who also left National Concord as General Manager Sales and Circulation was also Managing Director and Editor-in-Chief of the now rested Monitor Newspapers owned by the late Aare Musulumi of Yorubaland, Azeez Arisekola Alao.

Tella had, at various times, served as Chairman of the Osun state Broadcasting Service and Chairman of the State Hajj commission. He later served as a national commissioner at the National Hajj Commission of Nigeria.

The veteran journalist also contested to become a member of the House of Representatives in 2011 but lost the bid to represent the people of Iwo/Ayedire/Ola-Oluwa Federal Constituency at the time.

Speaking at the unveiling of the book Iwo and the Dungeon of political Poverty in Iwo on Saturday, Tella lamented that the ancient town has delivered huge votes to contribute to the electoral successes of past contenders with little or nothing to show for it in terms of development.

According to Tella in his book, the people of Iwo have not benefitted from politics due to factors which he recognised as poor educational background, lack of economic powers, treachery and the practice that makes every political appointee to return home after serving one term.

On poor education, Tella wrote, “At the early stage of national political development in Iwo, only very few read beyond primary education who ended up being mostly primary school teachers unlike the emerging politicians from Ijebu, Egba, Ijesa, the Ekiti areas of the old Wester Region.”

Tella wrote that the poverty

of European education was traced to what he called “Islamic irredentism” explaining that “Iwo was a complete Islamized town since the close of the 13th century.”

He explained further, “The fear of evangelization and forceful conversion to Christianity made the people to shun the white man school.

Only few allowed their children to go to school and most of them were eventually converted. Iwo, therefore, needed high grade educated people to square up with their counterparts from the other major Yoruba cities and towns in the allocation of resources and sharing of political positions in the civil or public service.

The situation was compounded by poverty of economic power.

“Most of the known moneybags were stark illiterates with narrow economic base beyond their immediate environment. The moneybags were also not in reasonable numbers to back up the politicians of their time. Most of them were cocoa farmers/merchants, butchers (Alapata) and lorry owners/drivers compared with the Egbas, Ijebus, and Ijesas.

Many, if not all of them were not educated in Western education. Many of them however had Oriental and Islamic education.”

The author listed what he called “Manafiki” treachery and its linkage with politics in Iwo land as starting as early as 1954.

“The case of Lawyer Sanni Adiatu exemplified. Since then, till date, fratricidal rivalry, blackmail, and demonization of one another remains the stock in trade of Iwo Politicians. The “bring him down” syndrome remained intractable till the present day.”

.He said the rascality of semi-strong boys who became politicians used in the bring down power struggle, which was used during Action Group crisis of 1962, the demonization of the NNDP led by Chief S. L Akintola SLA persists till today in Iwo more than any other town in the Southwestern region.

“Few prominent Iwo indigenes who found themselves in politics were rudely brought down,” he said

He also cited what he called “anachronistic single term syndrome for elective or executive office holders in two” saying that this has caused a turnover of political office holders to be higher in Iwo more than anywhere else in Nigeria, with one-term only for elected legislator at the state or federal levels.

He said this turnover has been responsible for the inability of Iwo individuals to attain higher positions in politics.

“There is no way for Iwo to produce speaker, deputy speaker, or principal officers of the state or national assembly.

“This has negatively affected the fortunes of Iwo land in both resource and project allocation. A newly elected legislator who is not politically mentored or educated will need to leam the process and ethics of lawmaking to make reasonable contributions and impact. It may take up to two years to leam the rope. Thus, the time to struggle re-election may not allow him/her to concentrate on the demands of law making. The National Assembly is not supposed to be a place for political neophytes or Lilliputians. Highly experienced people are needed to a functional legislature.”

Barrister Femi Kehinde, who is the Director of Akoosa Publishers, which published the book, the inability of the town’s political elites to come together to push for the glory of the ancient town represent a great calamity.

Speaking at the unveiling of the book, Kehinde, a former member of the House of Representatives said, “The book is an expose of the great calamities that hve befallen iwo. I am an indigen of Iwo and when I look back, I know Iwo can be better.”

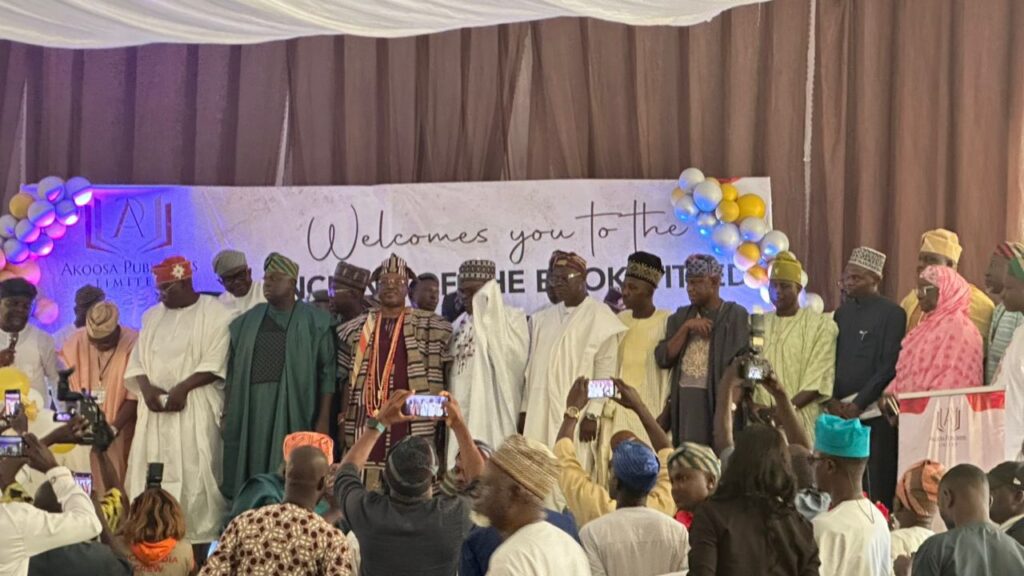

At the event on Saturday were political functionaries past and present. They include Governor of Osun, Demola Adeleke who was represented by one of his commissioners, Sunday Oroniyi; a former deputy governor in the state Senator Omisore, National Secretary of the All Progressive Congress, Basiru Ajibola, former National Commissioner, Independent National Electoral Commission, Prof Lai Olurode, a former Special Adviser to Governor Rauf Aregbesola, Mr. Semiu Okanlawon, former Chairman of the National Hajj Commission, Barr Dhikrlah Hassan; governorship aspirants in Osun – Chief Akin Ogunbiyi, Prince Dotun Babayemi, state chairman of the APC, Sooko Tajudeen Lawal, former Senator representing Osun West, Adelere Oriolowo and others.

In his review, Vice Chancellor of the African School of Economics, Abuja Prof Mahfouz Adedimeji described the book as a major clarion call for political gladiators from the town (where he also hails from) to do the needful and priotise the interests of the town above personal interests.

He expressed appreciation to the author for considering it germane to lay bare issues that had bedevilled the politics of the town in decades noting that the content of the book should ignite a new thinking.