India’s Adani Group has seen its market value plunge after a US investment firm made fraud allegations against it. Can its ambitious growth plans survive?

How did the market rout unfold?

Until two weeks ago, the ports-to-energy conglomerate which operates seven publicly traded companies had a combined valuation of $220bn.

But since 24 January, when short seller Hindenburg Research accused the group of “brazen” stock manipulation and accounting fraud, its valuations have nearly halved. The group’s founder Gautam Adani has seen billions wiped off his personal wealth and has dropped out of the list of the world’s top 20 richest people.

The Adani Group has denied the allegations, calling them “malicious” and “baseless” and says it plans have not changed. But investors are clearly still nervous.

On Monday, the group said in a statement that it would prepay loans worth $1.1bn, taken using shares as collateral, ahead of their maturity date next year. This, it said, was partly due to “continued market volatility” and to assure investors that the group’s promoters would “prepay all shares-backed financing”.

Last week, the group also called off its secondary share sale. The 2.5bn (£2bn) it had raised was meant to pay off debt and fund projects, including airport renovation, expressway construction and an ambitious green hydrogen ecosystem.

Why do falling share prices matter?

They indicate investors are losing confidence in a company.

Analysts are now watching to see how the stock price slide affects the company’s operations, cash flow and expansion plans.

“Most of their ambitious projects will have to be heavily scaled back in ambition and timetable, because they will have next to no capacity to raise funds right now,” says Tim Buckley, director at Climate Energy Finance, a think-tank that works on financial issues related to transition from fossil fuel to clean energy.

It could borrow money to fund projects and acquisitions – a common strategy for infrastructure companies, which helped fuel the Adani Group’s rapid growth.

But the group’s debt has grown at a faster pace than revenues and profitability, which some fear could raise risks of a default – a concern flagged by both the Hindenburg report as well as some analysts.

Can the Adani firms just borrow more money?

The group already has total debt of nearly two trillion rupees ($24bn; £20bn) – it almost doubled over the past three years as Mr Adani’s ambitions extended to areas such as 5G and green hydrogen.

Nearly two-thirds of Adani’s debt is from overseas sources such as bonds or foreign banks, according to a report by global brokerage Jefferies.

READ ALSO:

Until now, the group has mostly raised funds by using its infrastructure assets or shares as collateral. But with stock prices plunging, the value of this collateral has also dipped. The private wealth units of two big banks, Credit Suisse and Citigroup, have stopped accepting Adani bonds as collateral, Bloomberg has reported.

Many Indian banks have also loaned billions of dollars to companies linked to the group and state-owned insurance firm Life Insurance Corporation of India has invested in it.

Market observers say that the Hindenburg report and the reaction to it will make lenders cautious – which means loans could become costlier.

“There is pressure on the company’s credibility. It will make it extremely difficult to raise fresh loans, especially in the overseas market,” an Indian corporate banker said on condition of anonymity as he didn’t want to be seen commenting on the Adani Group.

Another observer, a former banker with an international wealth fund, said that the group may be forced to delay some projects until the issue settles down. He also did not want to be named.

The BBC sent a list of questions to the Adani Group. A spokesperson replied: “All our ongoing projects continue according to the plan. Adani Group’s core fundamentals remain unchanged.”

Which Adani projects could be at risk?

Scrutiny on the group has now increased. Investors and credit rating agencies are closely assessing its ability to raise money and repay loans.

S&P Global Ratings has downgraded its outlook on two Adani companies to negative.

“New investigations and negative market sentiment may lead to increased cost of capital and reduce funding access for rated entities,” it said.

In a video statement after the group’s share sale was called off, Mr Adani had said that its balance sheet was “healthy and assets robust”. He added that the group has an “impeccable track record of fulfilling our debt obligations”.

But credit rating agency ICRA said in a statement last week that the group’s large, debt-funded capital spending programme remains a key challenge.

Most of the group’s capital-guzzling new businesses such as green energy, airports and roads are housed under flagship company Adani Enterprises Ltd (AEL) and depend on it for funds. AEL has enough cash but could come under pressure if it has to pay interest for even its subsidiaries.

Some of the group’s firms will be shielded from the current volatility because they own and operate strong physical assets such as ports, airports and factories.

“Adani Ports and Adani Power are the strongest and most well-capitalised [firms], which means their assets are backed by long-term government contracts. Most of the loans taken by these companies are against these revenue and profit-accruing assets,” says the corporate banker quoted above.

However, this isn’t the case for some of the group’s newer businesses.

Companies such as Adani Gas and renewable energy arm Adani Green already have immense debt on their books and are still building up their cash flows. This could make them more vulnerable to market shocks and reduce their creditworthiness.

The banker points out that while the prices of bonds issued by Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone Ltd have fallen only marginally, those issued by Adani Green had lost more than a quarter of their value in three days.

What options does Adani have?

Deferring new projects and selling some assets to raise money could be a way out.

ICRA has said that some of the planned capital spending is discretionary in nature and can be deferred, depending on how much liquidity it has.

“The company has built assets that are valuable to a developing country like India, and there will be many strategic investors interested,” said a corporate adviser who didn’t want to be named.

Some analysts remain optimistic.

“I have seen varied operating [Adani] projects from ports, airports, cements to renewables which are solid, stable and generating a healthy cash flow. They are completely safe from the ups and downs of what happens in the stock market,” says Vinayak Chatterjee, an infrastructure expert who is founder and managing trustee of the Infravision Foundation.

Analysts are also watching to see if there will be a regulatory enquiry into the group’s corporate governance. The issue has also set off a political row over Mr Adani’s perceived closeness to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, which both deny.

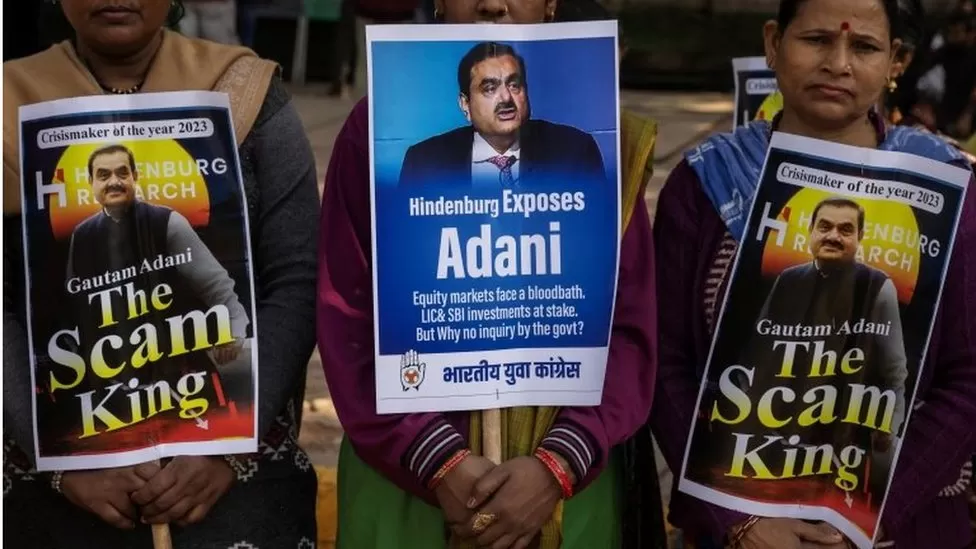

On Monday, the main opposition Congress party held protests across the country, demanding an investigation into the allegations.

Mr Buckley says that as pressure mounts, the Adani Group’s ability to win government contracts easily to ramp up revenues will be challenged. It will also find it difficult to restore its credit credibility.

Since the group has to repay a significant amount, it will have to do a strategic asset sale, he says.

Source: BBC News