Arabs are losing faith in democracy to deliver economic stability across the Middle East and North Africa, according to a major new survey.

Nearly 23,000 people were interviewed across nine countries and the Palestinian territories for BBC News Arabic by the Arab Barometer network.

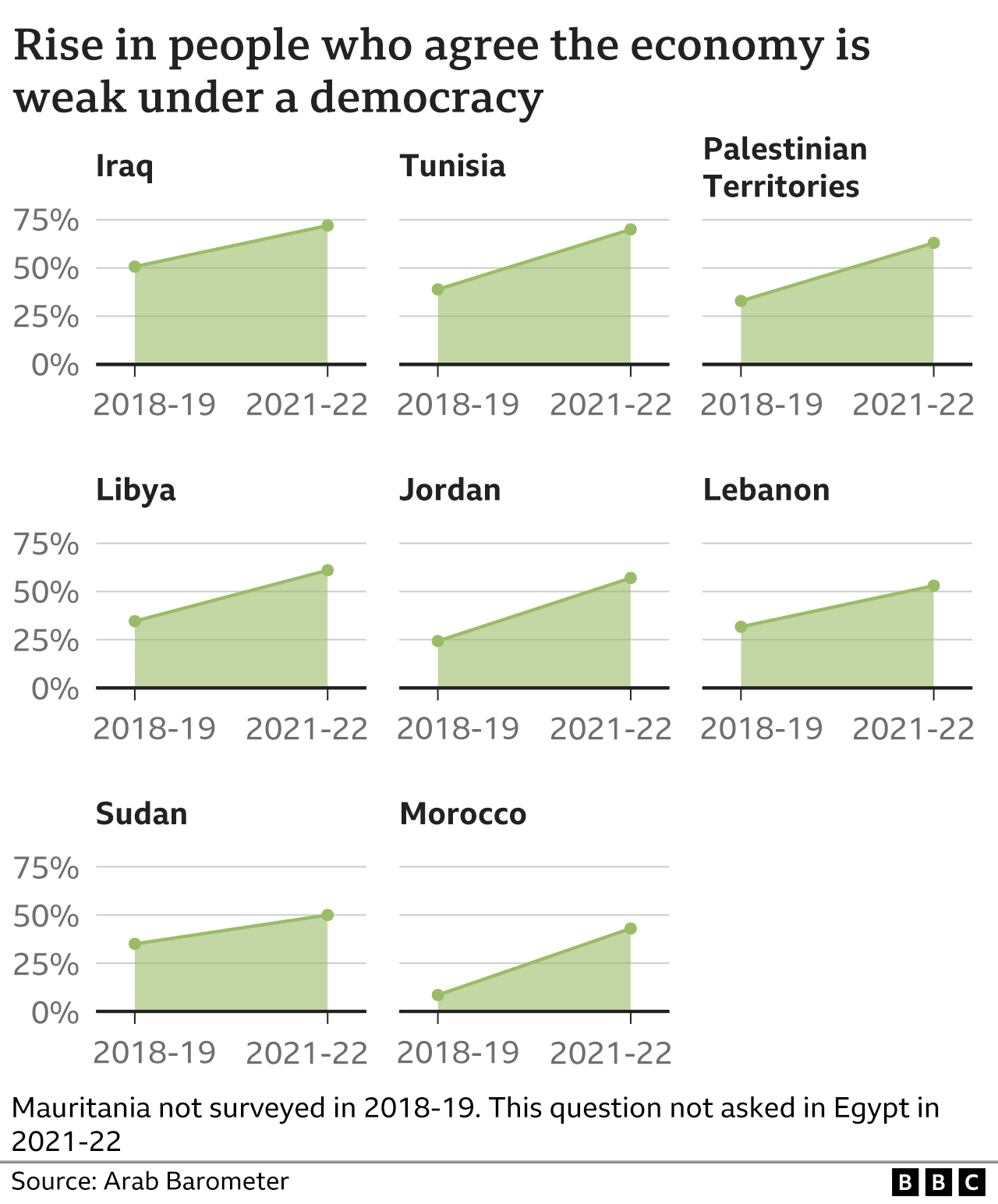

Most agreed with the statement that an economy is weak under a democracy.

The findings come just over a decade after the so-called Arab Spring protests called for democratic change.

Less than two years after the protests, just one of those countries – Tunisia – remained a democracy, but a draft constitution published last week could push the country back towards authoritarianism, if approved.

Michael Robbins, director of Arab Barometer, a research network based at Princeton University which worked with universities and polling organisations in the Middle East and North Africa to conduct the survey between late 2021 and Spring 2022, says there has been a regional shift in views on democracy since the last survey in 2018/19.

“There’s a growing realisation that democracy is not a perfect form of government, and it won’t fix everything,” he says.

“What we see across the region is people going hungry, people need bread, people are frustrated with the systems that they have.”

Across most of the surveyed countries, more than half of respondents, on average, agree with the statement that the economy is weak under a democratic system.

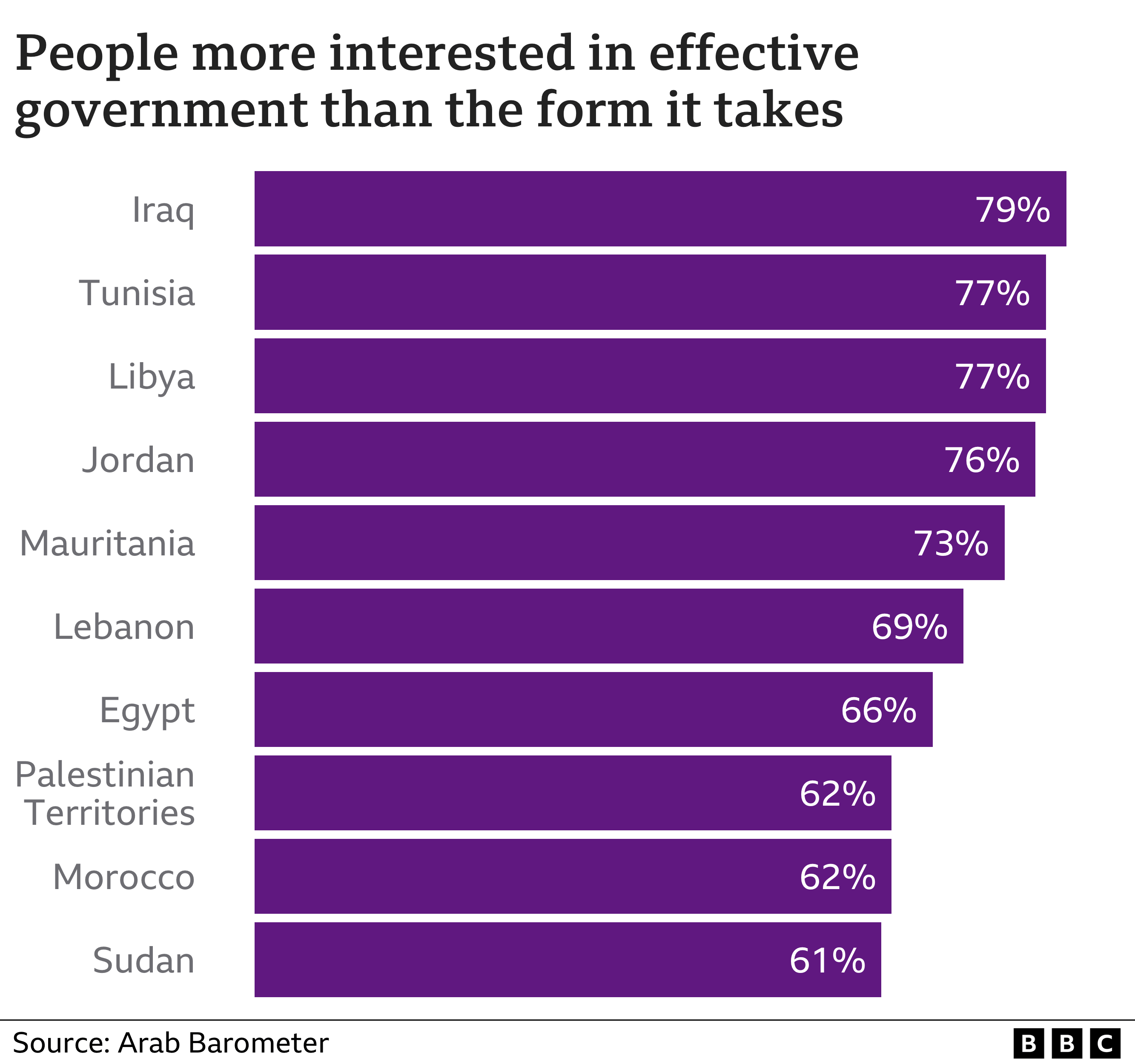

In every country surveyed, more than half also say they either agree or strongly agree that they are more concerned about the effectiveness of their government’s policies, than they are about the type of government.

According to the EIU Democracy Index, the Middle East and North Africa is the lowest ranked of all regions covered in the index – Israel is classed as a “flawed democracy”, Tunisia and Morocco are classed as “hybrid regimes”, and the rest of the region is classed as “authoritarian”.

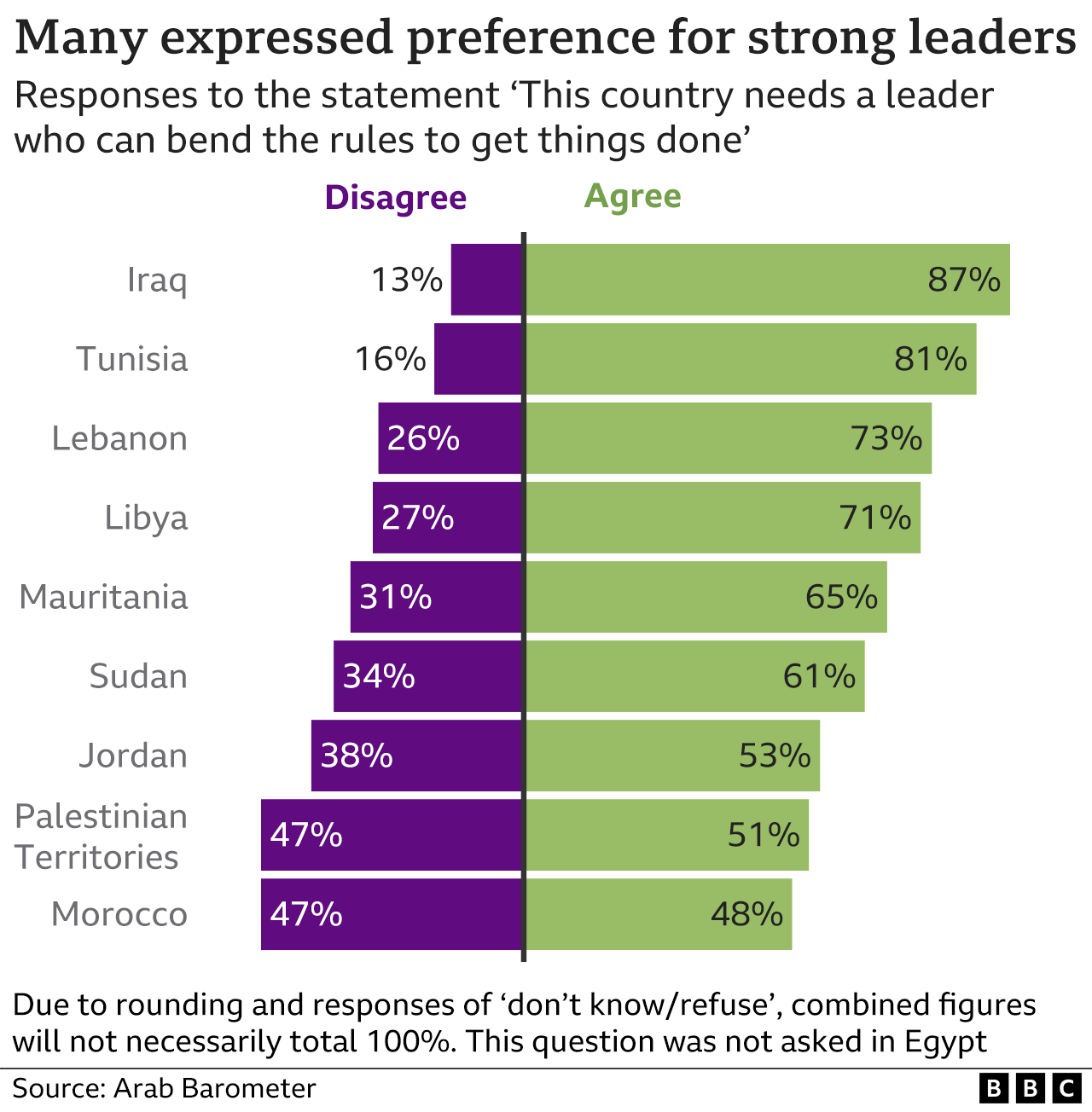

In seven countries and the Palestinian territories, more than half of respondents to the Arab Barometer survey agree with the statement that their country needs a leader who can “bend the rules” if necessary to get things done. Only in Morocco do fewer than half agree with that statement. However there is also a sizeable proportion of people disagreeing with the statement in the Palestinian territories, Jordan, and Sudan.

In Tunisia, eight in 10 of those surveyed agree with the statement, with nine in 10 saying they supported President’s Saied’s decision to sack the government and suspend parliament in July 2021, which his opponents denounced as a coup but he said was necessary to overhaul a corrupt political system.

Tunisia was the only country that managed to form a lasting democratic government following the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings. However, Tunisia appears to be slipping back into an authoritarian rule under President Saied. According to the EIU democracy index for 2021, the country fell 21 places in the rankings and has been reclassified as a “hybrid regime” rather than a “flawed democracy”.

The survey in Tunisia was conducted between October and November 2021. Since then there have been protests against the president, as he has tightened his grip on power by dissolving parliament, taking control of the electoral commission, and pressed ahead with holding a referendum on a new constitution which many say will boost his authority. The country’s economy has meanwhile sunk deeper into crisis.

“Now, unfortunately, for Tunisia, it’s reverting to authoritarianism, or what we call democratic backsliding, which is a trend across the world today,” says Amaney Jamal, co-founder of Arab Barometer and dean of the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs.

“I think one of the key drivers is not a commitment to authoritarianism or an authoritarian political culture, it’s really a belief now that democracy has failed economically in Tunisia.”

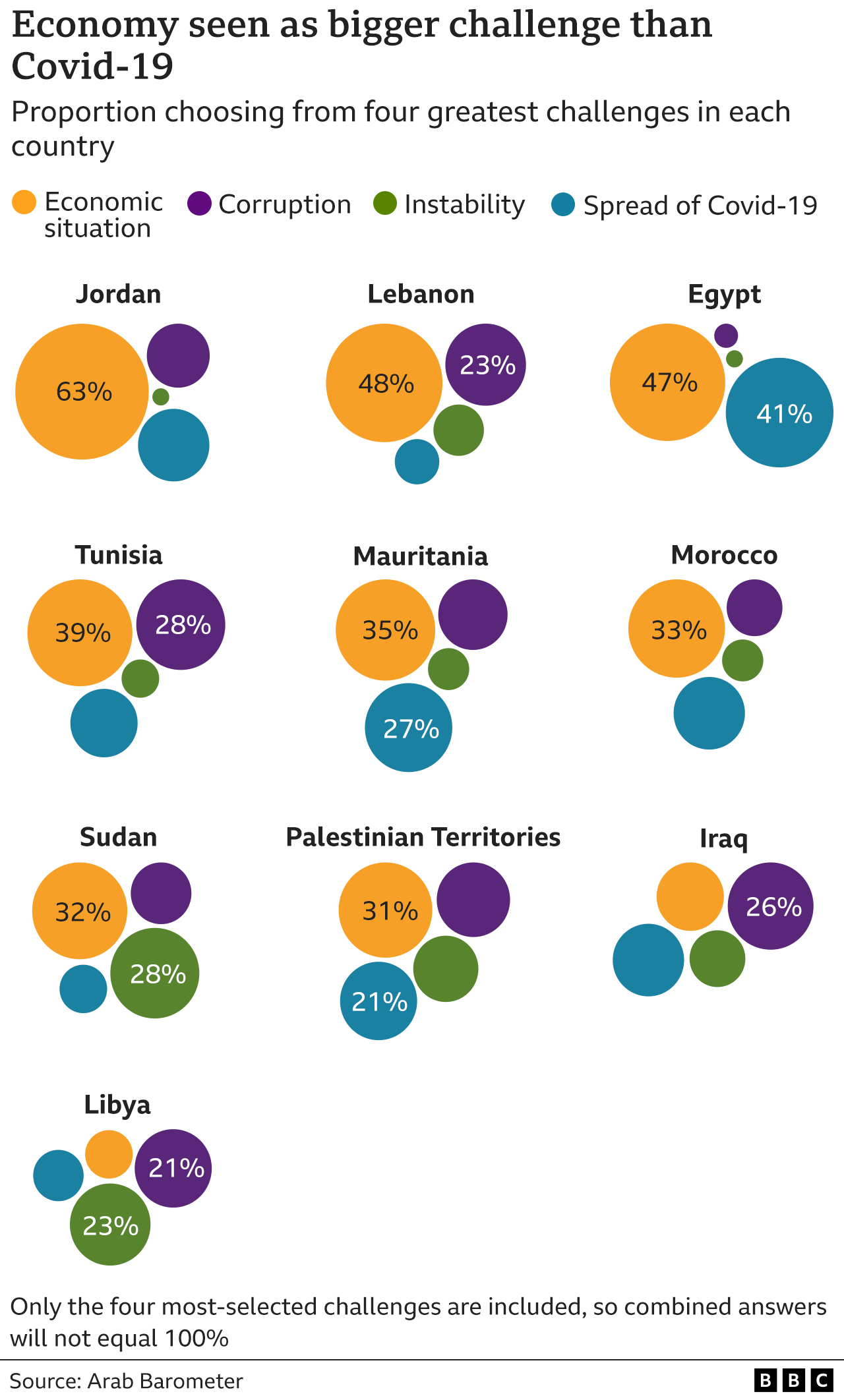

The economic situation is seen as the most pressing challenge for seven countries and the Palestinian territories, ahead of corruption, instability, and the spread of Covid-19.

Only in two countries is the economic situation not seen as the most crucial issue – in Iraq, where it is corruption, and in war-torn Libya, where it is instability.

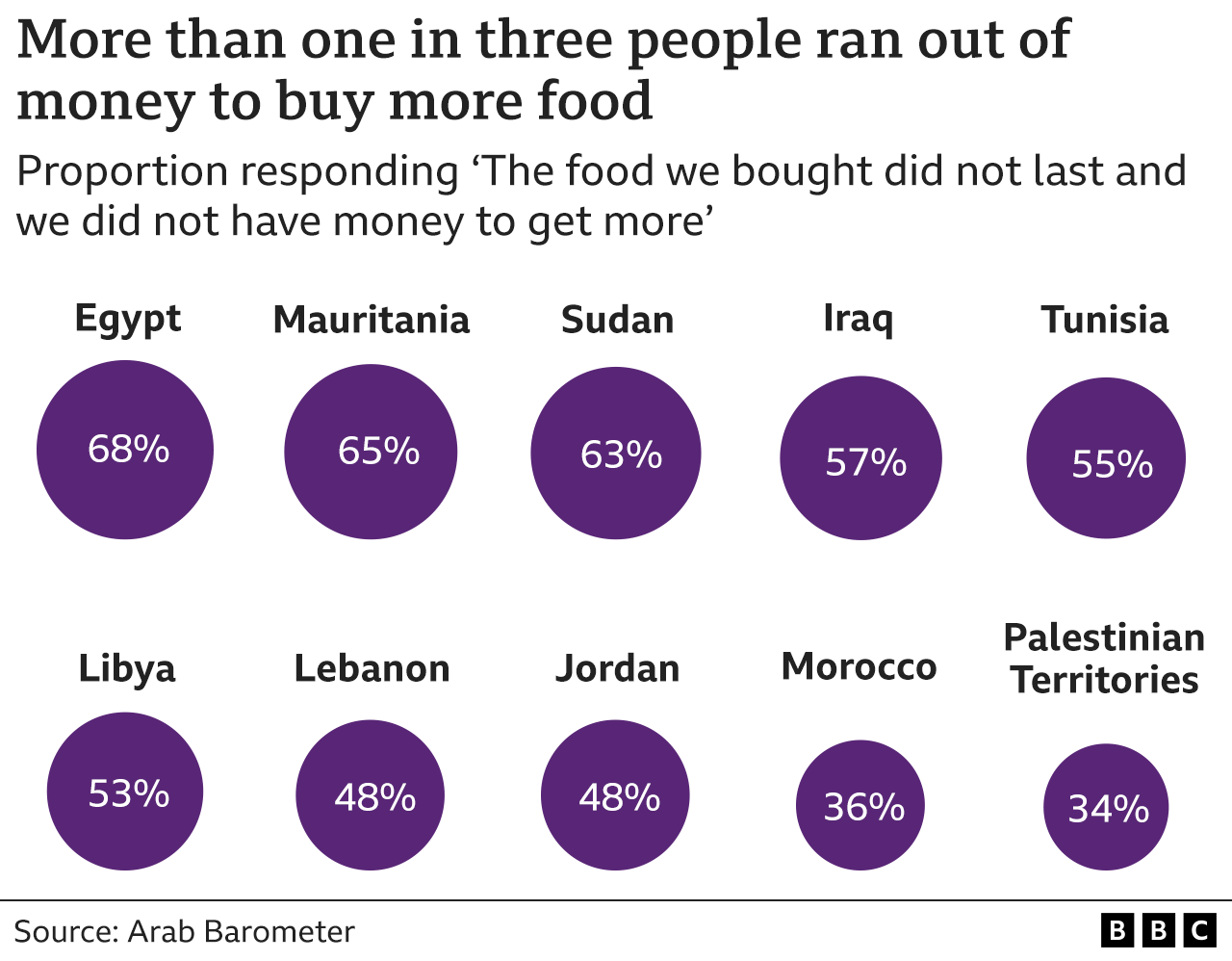

At least one in three people in every country surveyed agree with the statement that, over the past year, they ran out of food before they next had sufficient funds to buy more.

The struggle to keep food on the table was most acutely felt in Egypt and Mauritania, where around two in three people said this happened sometimes or often.

The survey was for the most part conducted before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, which has further exacerbated food insecurity across the region – particularly for Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia – which heavily rely on Russian and Ukrainian wheat exports.

The survey’s respondents who reported being unable to buy more food when they ran out were less supportive of democracy in a number of the countries surveyed, especially in Sudan, Mauritania, and Morocco.

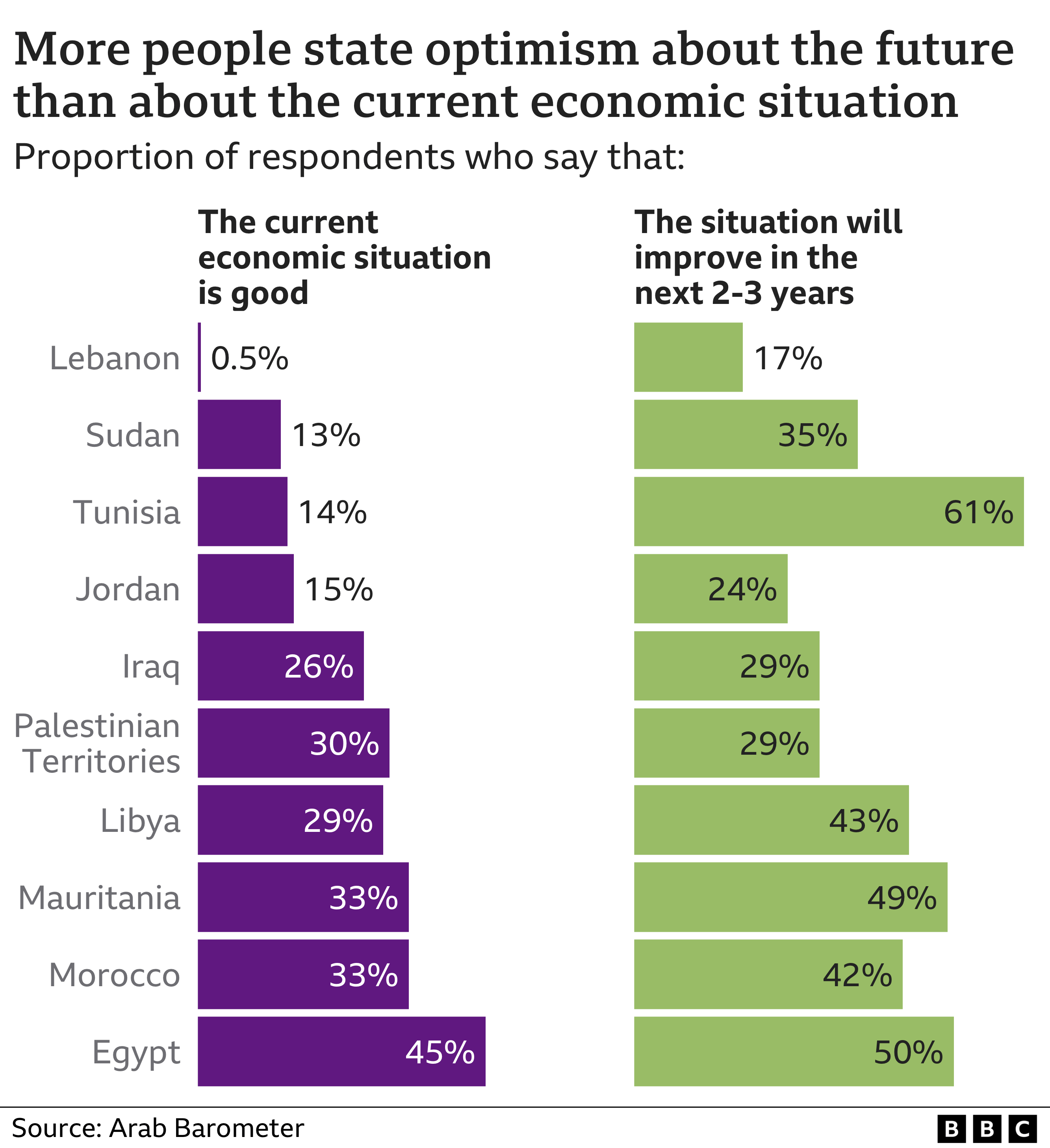

The economic outlook is bleak across the region, with fewer than half of all respondents willing to describe the economic situation in their country as good.

Lebanon is ranked lowest out of all the countries in the survey, with less than 1% of Lebanese questioned saying that the current economic situation is good. The World Bank has described Lebanon’s economic crisis as one of the most severe in the world since the mid-19th Century.

Overall most people don’t expect the economic situation in their country will improve in the next few years. However there is some optimism. In six countries, over a third of surveyed citizens say the situation will be better or somewhat better in the coming two to three years.

Despite the economic turmoil currently gripping Tunisia, its respondents are the most hopeful about the future, with 61% saying things will be much better or somewhat better in a few years.

The future is “uncertain”, says Dr Robbins of Arab Barometer. Citizens in the region may be looking to alternative political systems, such as the Chinese model – an authoritarian one-party system – that he says has “brought a huge number of people out of poverty in the last 40 years”.

“That type of rapid economic development is what many people are looking for,” he says.

Additional data journalism by Erwan Rivault.

Methodology

The survey was carried out by the research network, Arab Barometer. The project interviewed 22,765 people face-to-face in nine countries and the Palestinian territories. The Arab Barometer is a research network based at Princeton University. They have been conducting surveys like this since 2006. The 45-minute, largely tablet-based interviews were conducted by researchers with participants in private spaces.

It is of Arab world opinion, so does not include Iran, Israel or Turkey, though it does include the Palestinian territories. Most countries in the region are included but several Gulf governments refused full and fair access to the survey. The Kuwait and Algeria results came in too late to include in the BBC Arabic coverage. Syria could not be included due to the difficulty of access.

For legal and cultural reasons some countries asked to drop some questions. These exclusions are taken into account when expressing the results, with limitations clearly outlined.

You can find out more details about the methodology on the Arab Barometer website.

Source: BBC News