A network of Nigerian separatists based outside the country is using social media to call for violence and incite ethnic hatred against opponents of Biafran independence, a BBC investigation has found.

Warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of violence

In a Facebook live broadcast to her more than 40,000 followers, Efe Uwanogho, also known as Omote Biafra, shouts hate speech directly into the camera.

The front of her leather jacket features a patch of the Biafran flag, with its red, black and green tricolour and half a rising sun.

“Go after these mighty saboteurs… Those are the people that need to be beheaded. Those are the people that need to be burnt to ashes,” she says.

She’s calling for attacks against those considered enemies of the campaign for Biafran independence, which would create a breakaway state in south-east Nigeria.

The campaign has a bloody history.

In 1967 separatists from the mainly Igbo region declared independence for the Republic of Biafra. They fought and lost a three-year civil war against the Nigerian government in which more than a million died, mainly on the separatist side.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESMore than half a century later, social media is a new frontline for those who are continuing the struggle.

Ms Uwanogho is among them. She’s a so-called “media warrior” for the separatist group known as the Indigenous People of Biafra (Ipob).

She broadcasts from Italy, beyond the reach of Nigerian authorities. In Nigeria, Ipob has been banned and designated a terror group. Ipob insists it is a peaceful movement.

The BBC’s investigation revealed many other influential Ipob supporters also operating outside the country, openly promoting disinformation and inciting violence on social media from across Europe, the US, Asia and other parts of Africa.

Nigerian investigative journalist Nicholas Ibekwe describes the group’s online operation as an “organised troll farm”.

“Social media has been Ipob’s most successful tool in achieving most of what it wants to achieve today,” he says.

Some supporters of the group have as many as 100,000 followers on social media.

We don’t know if any of Ms Uwanogho’s followers took action based on her online calls for violence against officials in south-eastern Nigeria.

Ms Uwanogho did not respond to a request for comment on this story.

But on the ground, the violence is real, with dozens of officials killed in attacks already this year in violence described by President Muhammadu Buhari as “deeply distressing”.

Nneka Igwenagu is another “media warrior” fighting for the Biafran cause, based in the UK.

In a Facebook live broadcast from London in late 2021, she targets a youth group in Anambra, south-east Nigeria, which had been resisting pressure from Ipob for people in the region to shut down businesses and schools in solidarity with the group’s detained leader Nnamdi Kanu.

IMAGE SOURCE, AFP

IMAGE SOURCE, AFPMr Kanu is currently being held by Nigerian authorities and faces terror charges, which he denies.

Speaking in Igbo, the most widely spoken language in south-eastern Nigeria, Ms Igwenagu refers to them as “chickens”, saying:

“All of you are not supposed to be alive… A chicken that ate its eggs, don’t you see it is not supposed to live?”

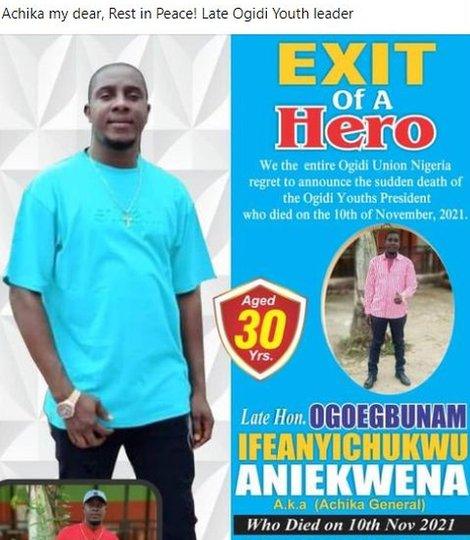

A few weeks after the broadcast, the leader of the youth group she was referring to was shot and killed. Nobody has been charged over his death.

We contacted Ms Igwenagu for a comment on this investigation, but received no response.

One of the ways the media warriors attempt to avoid censorship is to switch into local languages that are less well moderated.

This tactic is made explicit in one video we found. Okenna Okechukwu, also known as Biafran Child, speaks in Igbo when calling for the beheading of a critic, before switching to English and explaining to his followers:

“Why I am saying this in my dialect is because I don’t want them to stop me. I don’t want them to block me on this page.”

David Ajikobi, Nigeria editor of fact-checking organisation Africa Check, says that the lack of moderation of extreme content in local languages is a major issue, not limited to Nigeria.

“We’ve also seen this in India, in Ethiopia, where crises are happening, people are using local language because they know that if they use English they will be flagged and will be removed from the platform.”

Despite the violent nature of many of the online posts we found, moderation by social media platforms is inconsistent.

In line with Facebook’s own process, our team reported broadcasts by Efe Uwanogho and Nneka Igwenagu for containing violent content. We initially received a notification that the platform had decided not to take the videos down.

It was only later, when the BBC shared links to the posts directly with Facebook that they were removed. But violent broadcasts from the same accounts, as well as others, remained online at the time of publication.

Stoking tension

Facebook’s parent company Meta told us in a statement that calling for violence on its platform was unacceptable. It said that it had 15,000 people reviewing content in more than 70 languages – including Igbo.

Our investigation also found Ipob supporters spreading disinformation to stoke tension between different ethnic groups in Nigeria.

Media warriors pit ethnic Igbo people, who are mainly Christian and from the south, against those from the Fulani ethnic group, who are predominantly Muslim and from the north.

In another Facebook live broadcast, Ms Igwenagu warns her followers that Fulani herders and other northerners who have moved to “Biafraland” are on a “mission… to exterminate, kill maim, wipe [out] all of us”.

Payment for posts

Although there have been clashes between Fulani herders and communities in the south-east, there is no evidence of the sort of conspiracy that Ms Igwenagu and others are alleging.

This violent rhetoric may be driven by a desire for Biafran independence, but our investigation also found evidence of financial incentives for those involved.

We found videos in which media warriors admitted to being paid, either by Ipob or by supporters, for the work they do and we saw other broadcasts in which bank details for Ipob were shared to solicit donations from followers.

Journalist Nicholas Ibekwe is among those who are critical of social media companies to tackle the violent threats being made on their platforms.

“It seems Facebook has really really gone to sleep. It does not think that these comments, these posts that they do on Facebook have consequences.”

Meanwhile, attacks continue on the ground.

On 30 April, Nigerian soldiers Audu Linus and Gloria Matthew were on their way to get married in a traditional ceremony in Imo state when they were abducted, tortured and killed by unidentified attackers.

Footage showing the couple’s killing, which the Nigerian president has blamed on Ipob, then went viral.

A conspiracy theory was then widely shared by some Ipob supporters claiming that the footage was not real and the soldiers’ deaths had been staged.

The BBC has independently confirmed the deaths of the two soldiers with family members.

Ipob has denied any involvement in the killing.

We contacted Ipob’s leadership with our findings from this investigation. The leadership replied, but did not provide a response.

We contacted all of the media warriors featured in this story to ask for their comments, but had no response.

Source: BBC News